Blog / A better life, underground

- Date

- November 9, 2008

- Tags

Fable II is a bad game. If you like it, you’re a bad person. Consider it the ultimate moral judgment in a game that does little else.

This is clearly what the original Fable was supposed to be: a go anywhere, do anything RPG where your choices shape your character and the world around you. At first glance they’ve succeeded. The levels are larger, the combat is better, and your choices of what to do are more varied and interesting. But this doesn’t excuse the obvious lack of polish and thoughtfulness in every aspect.

Consider the opening cinematic: with epic Harry Potter-esque music humming, a sparrow flies through the woods and into the gorgeous city of Bowerstone. It perches on a roof, looks around, and craps right on your character’s head. You gain the nickname “Sparrow” and a clear message from Peter Molyneux: I will shit on you. Whatever happened to Will Wright’s Pee?

“Sparrow” is a beggar child in a world Charles Dickens would have found oppressive. Your older sister runs you through an hour of tutorials only to be shot and killed. You are merely shot and tossed out a tower. The long fall, an old video game cliché, guarantees your survival. Nursed back into health by the creepy narrator lady, you emerge from some gypsy camp as a young adult on a quest for vengeance.

If you so choose. Me, I couldn’t wait to tell the main quest to go eff itself. The writing in Fable II isn’t bad, but it’s too grandiose for my tastes. They did the absolute minimum to bond you to your sister and I was glad to be rid of her. What you are supposed to bond to is your stupid dog.

You meet the dog in the intro and he stays with you throughout the entire game. The deal is that your dog will turn good or evil depending on your moral decisions. He’ll help out in combat and point out treasure and dig spots in the world. You can be nice or mean to your dog, play fetch, give him treats, whatever. The reality is that your dog can’t path find worth a damn, has even less meaningful interactions than the robotic townspeople, and is pointless in combat. Though I’ll admit that he’s spotted a few treasure chests I overlooked.

Puppy’s path finding problem is part of a larger epidemic. The townspeople walk around idiotically, sure, but your player is the top offender. It feels like your shoes are dipped in butter. No matter where you are or what you’re doing, your character slides around, maddeningly imprecise to control. Your dog has a similar issue: he gets stuck on all sorts of obstacles. Sometimes he’ll warp ten feet ahead and run in circles. Or clip through your character, his snout poking through your knee. If I have problems just walking around in a game, I can’t enjoy anything else.

Okay, so I did enjoy the combat. It’s been decried as a one button mash-a-thon, but if you’re bored you’re not doing it right. Your character’s sloppiness is less of an issue and changing between melee, ranged weapons and magic on the fly is great fun. The only problem is that it’s too easy. So long as you can maintain some range between you and your target, fighting is a cinch. You’ll also have these strange brawls where a dozen guys surround you but only one bothers to attack at a time. As you mop up small armies by your lonesome, your incredulity meter rises dangerously.

But combat isn’t the main draw of Fable II. Go into the cities and target a civilian. They have names, likes and dislikes, favorite places, differing sexualities, jobs, homes, just like real people. They know your name, will congratulate or condemn your accomplishments, and may even fall in love, marry you and have your children. It’s unfortunate that all of them feel less human than Commander Data. Ladies, I ask you: would you marry a man if he did a heroic pose for ten seconds and then a little Russian dance? That’s all it takes. You can read a book to get more poses, which seems unnecessary until you realize that “have sex” is a hidden pose. That’s right: there’s no abstinence education required in this world, as nobody has kids until a book explains the mechanics.

You could probably write a feature list for this game that’s longer than a traditional review. There are actually jobs in this bloody game. Be a blacksmith, woodcutter or bartender. Own property and rent it out. Buy low and sell high. It’s a cliche to say the list goes on, but here it actually does. Sad that the interface can barely keep up. It’s slow to respond at all times and lacks many obvious features. Buying an outfit? You won’t know what it looks like on your body until money has changed hands. Is that sword better than the one you already have? Who knows? I rented out a house in Bowerstone and couldn’t find it in the local map. How are you supposed to play this mini-MMO if the menu is so tight lipped?

Maybe you’re supposed to play Fallout 3 instead. It features a wide open world full of possibility, except the only green you’ll ever see is on your LCD interface. Post-nuclear Washington D.C., the “Capitol Wasteland,” is a sea of gunmetal gray and dog shit brown. I’ll happily call it a worthy successor to the 2D Fallout games. Or the most expensive total conversion of the Oblivion engine ever made. While there’s not a single texture shared with the land of Tamriel, you still find rooms full of useless junk, a worthless third person view, sub-Mass Effect characters with that lovely neck problem, and identical controls to our last adventure in the Elder Scrolls universe. All it’s missing is Patrick Stewart as the voice of your father.

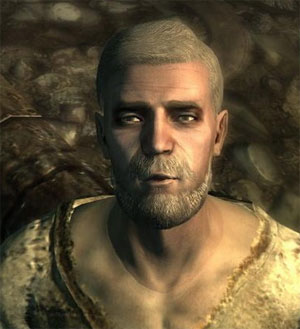

Ah yes. Fallout 3 has the most fascinating character development I’ve ever seen. It starts with your birth, in a POV shot of you, the infant, coming out of your mother’s womb. Your father wonders aloud if you are a boy or a girl. You, via the interface, answer him and choose your gender. Then the “gene sequencer” finishes determining what you’ll look like as an adult, and you go through the requisite cheek depth and eyebrow angle nonsense to shape your face. The screen flashes white and you’re a toddler, escaping the playpen to read a book called “You’re SPECIAL” and pick your stats for strength, perception, endurance and the rest. Then you’re ten, receive your Pip-Boy wrist computer and dialogue training. Then sixteen and taking your GOAT exam to determine your starting skills. It takes about as long as Fable II’s intro and tutorial, but it feels better and bonds you to your ever-present father.

When you’re nineteen he leaves the vault illegally and you go after him. Your first vista of the ruined landscape is incredibly powerful: the earth is dry and cracked, burnt-out cars litter the road, and houses and schools are shattered skeletons. The atmosphere of this awful place makes a powerful statement against nuclear war. Then again, considering how much fun the game is to play, maybe not.

What you do from here is up to you. Find the nearby settlement of Megaton and begin the search for Daddy-o. Wander around idly. Try and reach the Capitol building (hint: the Super Mutants will kill you). There are lots of quests to do, most of them rather complex and allowing for moral flexibility. I ran into a group of so-called vampires and was able to talk them out of converting a captive. I cleared a city of fire ants - literally giant ants that breathe fire - and helped a scientist reverse his awful mistake. Should you tire of mutilating yourself for nutty Minnesotan researcher Moira Brown in Megaton, go ahead and detonate the unexploded bomb in the middle of town. I doubt anyone would notice one more crater.

Combat is essentially the same as in Oblivion, though guns are obviously the big draw now. Your l33t skills are mostly for naught, as your character’s abilities determine your accuracy. Returning from the 2D games, amazingly, is the VATS system, which lets you pause time, pick a specific body part and roll the dice to calculate the hit. It feels remarkably natural, like a RPG version of bullet time. Plus, the cinematic camera is great fun when you score a headshot and a cranium goes flying. Perks like Bloody Mess guarantee dismemberment and contribute nicely to the hellish theme.

Buildings in Fallout 3 fascinate me. I love walking through bombed-out towns, reading scraps of signage and picking through people’s mailboxes. There’s a town on top of a highway on-ramp that seems like a cool place to live. An aircraft carrier has been converted into a floating fortress. Even the Washington Monument is here, and you can take an elevator to the top. You’ll spend a lot of time in grimy sewers and subways, yearning for the desolation above. Like the original Gears of War, you can use your imagination to turn back the clock and see what a great place this used to be.

In the second Gears of War you don’t need to use your imagination. Believe it or not, the impressive graphics of the original are even better, showcasing huge cities, complex architecture, and clear textures. Everything looks fantastic: the nearly ruined city of Jacinto, the Locusts’ underground caves, the abandoned research facility in the middle of nowhere with all the cobwebs. Some places - especially the research facility - look like what other games only wish themselves to be, Fallout 3 included. I stood in front of a bank of tubes full of green liquid and had to remind myself I wasn’t looking at concept art. If we still have room to go up from here, the future is going to be awesome.

So long as everyone keeps their mouths shut. Or rather, Dom keeps his mouth shut. His wife Maria is missing and about once an hour you get ten seconds of moping from the testosterone-fueled dope. This game and Crysis Warhead share perplexingly poor cutscene direction. There’s no shortage of cool stuff happening: choppers exploding, people fighting, but the sound effects seem muted and the music only swells up to your shins. President What’s-his-face delivered an impassioned speech about striking back against the Locust that compelled me to grab a Dr. Pepper until he was done yapping.

Gunplay feels the same, but the set pieces are constantly changing. March through a hospital. Tiptoe down a tunnel with a giant drilling machine providing light. Go through the belly of a giant worm and chainsaw through its arteries before the room fills up with blood. Disgustingly awesome scenarios await you.